Video interview with Haruka Kuroda

Choreographing the physical side of a performance

Costumes, sets, props – all that matters, she explains, when it comes to choreographing the physical side of a performance.

‘My role is about finding solutions that make sense for both the performer and the story.’

Working alongside Revival Director Jamie Manton, she sees herself less as a leader and more as a supporter.

‘Success is when the audience forgets you were ever there. I’m here to lift people, not draw attention to myself,’ she explains. ‘The director has a huge vision to carry. The singers are baring their hearts every night.

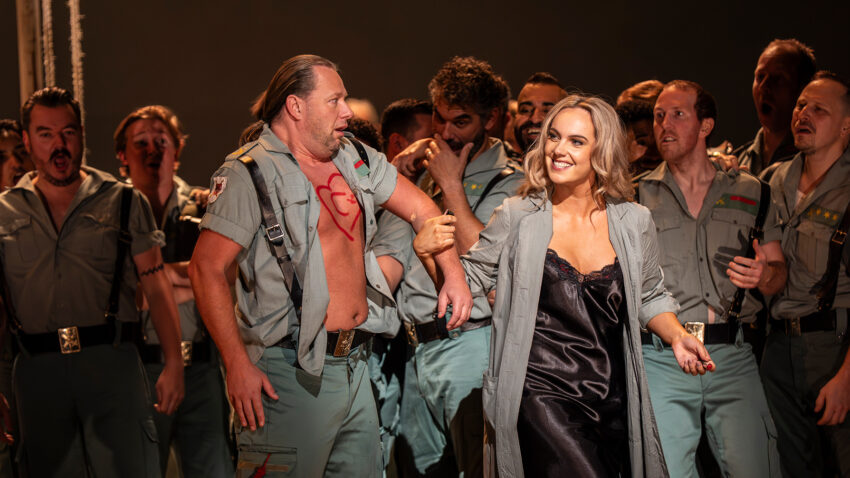

Showing the ugliness of the story

Manton’s revival leans into the grit of the 1970s, confronting misogyny and toxic masculinity head on. ‘We can make this production even uglier,’ Kuroda admits. ‘And it should be ugly, because these behaviours are ugly. Carmen’s freedom, her defiance, and the price she pays – none of that has lost its sting.’

My job is to help them feel safe, comfortable and authentic while doing that.’

For Kuroda, there’s little distinction between intimacy and violence. ‘The emotion, whether it’s passion for love or for murder, comes from the same place in a human. It’s just tuning it differently. That’s what I find so fascinating.’

How to stage violence and intimacy

The process begins with consent.

‘In the first few days, I run workshops – through games, exercises and conversations – that help the cast understand what consent looks like in practice,’

‘What it means for you, as an artist, to tell a possibly upsetting story. I want them to have the tools to carry on when I’m not there.’

Adjusting movements to protect voices and bodies

From there, the work becomes specific: clarifying physical boundaries, establishing “contracts” between performers, adjusting movements to protect voices and bodies.

‘Sometimes I’ll suggest a different way of staging a kiss, or a fight, that makes the moment more powerful without crossing boundaries,’ she explains. ‘It’s not about making things feel sexier or look cooler, though; it’s about authenticity, safety and story.’

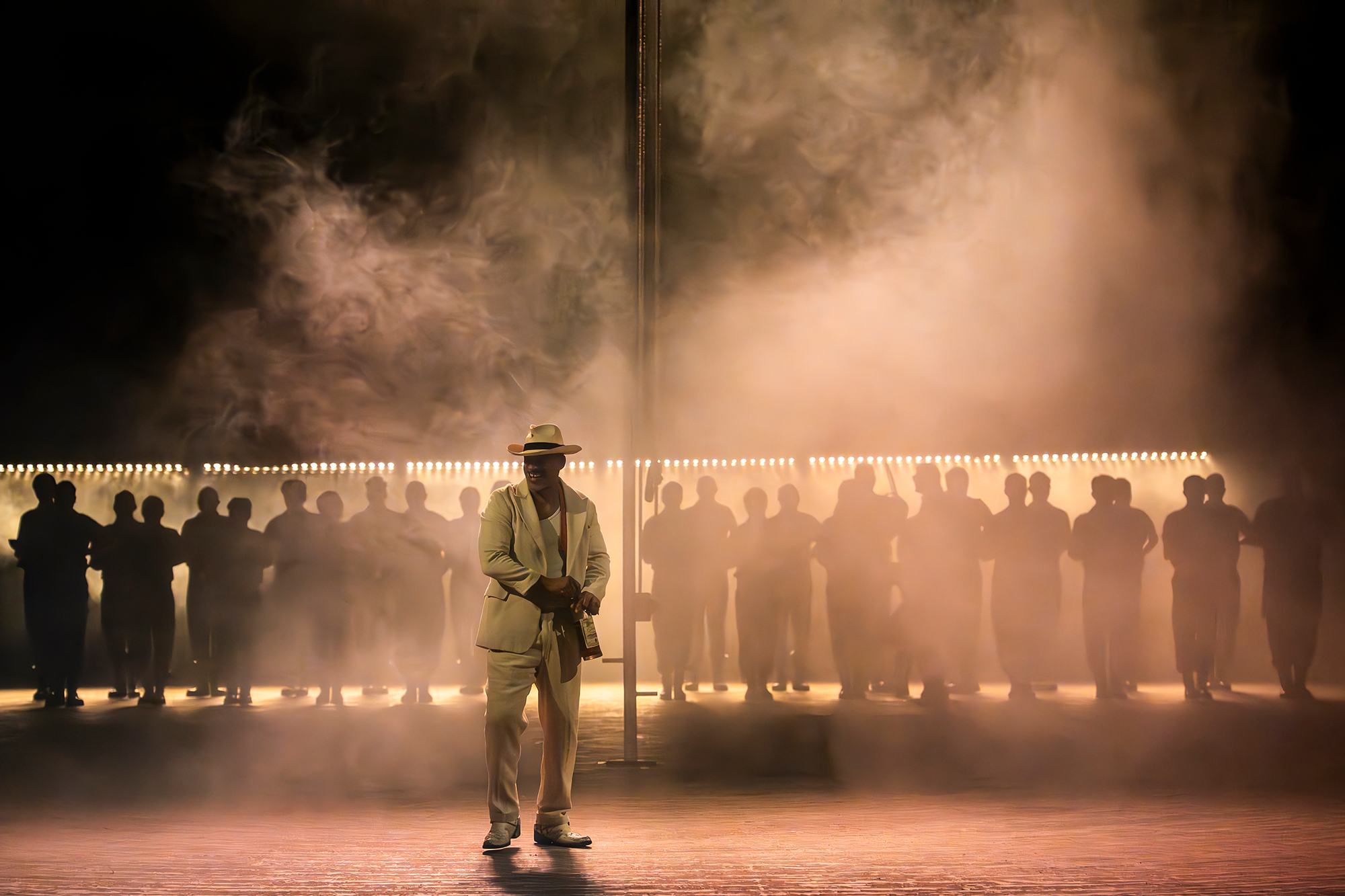

A relevant story for today

‘It’s a work of art steeped in history and it’s still so relevant. Some people argue that we shouldn’t tell these stories any more because of the culture we live in. But I believe we can – and must – tell them responsibly.

If audiences come away questioning, debating, feeling uncomfortable, that’s a good thing.’ If this production sparks conversation about misogyny, obsession, violence against women, that’s no small thing, adds Kuroda. ‘We want to get people talking.’

Working with children

This Carmen revival also includes children, which adds another layer of responsibility to Kuroda’s role.

‘The chaperones are our guides,’ she says. ‘We never assume what a child needs to feel comfortable. Clear communication is everything.

It’s about building trust – between me, the children, the chaperones – so that the young performers can enjoy being creative in a safe, supported environment.’ This makes for emotionally charged work.

A compassionate environment

‘I tell the cast on day one: this isn’t just my or the director’s responsibility. Everyone has to contribute to making the space safe and joyful.

Actors deserve to finish a production thinking “that was a wonderful experience”. That only happens if we learn to self-care and look out for each other.’

Telling the story truthfully

It’s not just the performers who need safeguarding; audiences must be considered, too. ‘One of the things Jamie [Manton] and I are focused on is preparing the audience for what they’ll see.

‘We want to be clear: there may be nudity, if nudity is needed. There will be violence, too, and the themes of Carmen are challenging.

‘We’re not here to soften Carmen. We’re here to tell this story truthfully. If it’s violent, it should feel violent. If it’s ugly, it should feel ugly. But always in a way that respects the artists and the audience.

What will audiences feel when they leave Carmen?

‘I hope they feel something,’ Kuroda says. ‘I hope they go home and talk about it with people they care about. Because theatre should make you feel, whether that’s pain, joy, outrage or delight. If we’ve done our job, they’ll leave invigorated and curious, carrying the conversation with them.’

For an opera that scandalised 19th-century Paris, Carmen remains shocking, thrilling and wholly necessary in 2025.

Thanks to voices like Kuroda’s, it can still challenge us – not by erasing its violence, but by confronting it with honesty, empathy and care.