Night’s caressing grip: Benjamin Britten and his themes of dreams and sleep

The worlds of sleep, dreams and nightmares, the unconscious, were all of powerful significance to Britten’s artistic life and fed into much of his creative work.

Composer Benjamin Britten distrusted working at night and spoke of dreaming as an important part of the process of composition: ‘it gives a chance for your subconscious mind to work when your conscious mind is happily asleep … if I don’t sleep, I find that … in the morning [I am] unprepared for my next day’s work’. He also admitted, without being specific, that dreams could also ‘release many things which one thinks had better not be released.’

Like many people, he experienced dreams about the deaths of family members, especially when a boarder at public school, and bad dreams could affect him for several days. In 1966, Britten recounted a dream – more a nightmare – to Shostakovich, in which he met Stravinsky, transformed into a monstrous hunchback, who pointed ‘with a quivering finger at a passage in [Britten’s recent] Cello Symphony’, and said, accusingly: ‘How dare you write that’. This was evidently a disturbing experience; but on another occasion Britten recalled a dream about meeting Schubert, a composer he revered and whose music, especially the song-cycle Winterreise, he was close to. In Britten’s dream Schubert blessed him, and Britten felt the effect of this subconscious experience for several days afterwards. No wonder Britten told a friend, ‘dreams are strange & remote’.

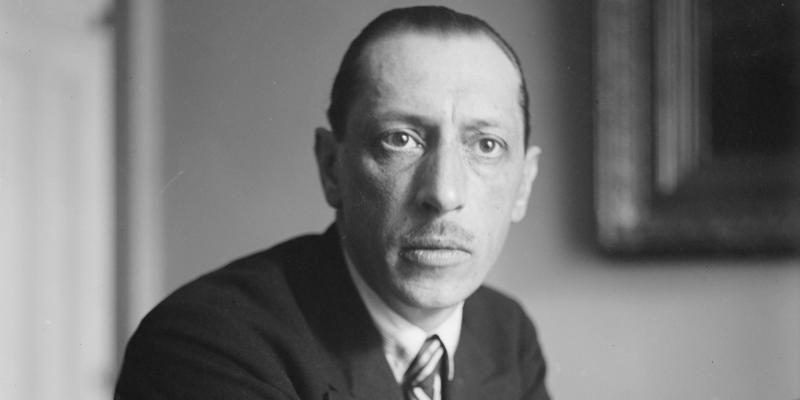

Russian composer Igor Stravinsky

The power of what poet W. H. Auden called ‘Night’s caressing grip’ is reflected throughout the Britten’s output: night-inspired compositions litter the entire range of his oeuvre, from instrumental nocturnes such as can be found in the early piano suite Holiday Diary (1934), through to the magnificent solo guitar piece, Nocturnal after John Dowland (1963), with its explanatory subtitle, ‘Reflections on “Come, heavy Sleep”’.

Virtually every one of Britten’s operas prior to A Midsummer Night’s Dream includes significant, often hauntingly beautiful and, occasionally, disturbing night music. Think of the nocturnal sounds of the primeval North American forest in Paul Bunyan (1941); the ‘Moonlight’ interlude from Peter Grimes (1945); the joy of Sid and Nancy’s twilight courting in Albert Herring (1947); the depiction of cool moonlight (piccolo in its lowest register) in Billy Budd (1951), on the eve of the condemned sailor’s execution; the Verdian-inspired garden scene in the second act of Gloriana (1953); and the deeply sinister, yet for Miles and Flora, alluring bumps in the night in The Turn of the Screw (1954).

Stuart Skelton sings the Great Bear and Pleiades from Britten's Peter Grimes

Video

Further aspects of the world of sleep and dreams are explored by Britten in his song-cycles with piano and with orchestra. A Charm of Lullabies (1947) is a song-cycle of invitations to go to sleep; and in his Pushkin cycle, The Poet’s Echo (1965), set in Russian for the great prima donna Galina Vishnevskaya, there is even a song devoted to insomnia.

The central works concerned with this preoccupation of Britten’s are the celebrated Serenade for tenor, horn and strings (1943), which ends with a setting of Keats’s invocation to sleep, and the later dreamscape, the orchestral song-cycle, Nocturne (1958), which in effect picks up where the Serenade ended. This is true in a literal musical sense: the principal motif of a rejected song from the earlier cycle, a setting of Tennyson’s ‘Now sleeps the crimson petal’, is identical to that of the ‘breathing’ ritornello of the Nocturne, announced at the cycle’s opening. Britten gave the manuscript draft of ‘Now sleeps the crimson petal’ to a friend in 1943 and the setting did not come to light until 1987. It says much for the workings of Britten’s subconscious that he hit upon the identical motif across a gap of fifteen years.

Both Serenade and Nocturne use an anthology of English verse selected and shaped by the composer, and should be considered as core-curricular in an appreciation of Britten’s response to nocturnal imagery. Both cycles look forward to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Britten’s most concentrated and elaborate musico-dramatic response to the world beyond daily reality.

Britten’s Nocturne culminates in a setting of Shakespeare’s paradoxical Sonnet 43, ‘When most I wink, then do mine eyes best see’. This turned out to be the composer’s first mature setting of Shakespeare, a somewhat remarkable fact given Britten’s fearlessness in the face of most well-known English poetry (Donne or Hardy, for example). But the Shakespeare sonnet is clearly significant when considered in relation to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both within the chronological context – Nocturne was written a year prior to the planning of the opera – as well as in terms of their shared subject matter.

ENO A Midsummer Night's Dream production trailer

Video

In an article for the Observer (reproduced in the ENO programme for A Midsummer Night’s Dream), Britten describes the hurried circumstances of his alighting on Shakespeare’s Dream for an opera for the Aldeburgh Festival; it is likely that his 1958 setting of Sonnet 43 led Britten back towards Shakespeare when searching for a suitable pre-existing text for a new opera to launch the refurbished Jubilee Hall in 1960. (In a 1960 BBC radio interview with Lord Harewood, Britten admitted ‘I had incidentally thought a few years ago of doing this same piece [i.e. Shakespeare’s Dream] as an opera’.)

The episodic nature of Shakespeare’s original made Britten and his life partner Pears’s task of compression and reorganization easier than it might have been with a more organically developed dramatic structure, and they were ever alert to the possibilities within the play for musical structures. The clarity of the structural arch of each the opera’s three acts is one of the work’s strengths, as is Britten’s achievement in balancing the hierarchy of the three character-sets in the opera, which are themselves underpinned by an association with particular instrumental sonorities.

The supernatural world of the fairies – Oberon, Tytania and the chorus of boys is characterized by high-pitched voices: counter-tenor, coloratura soprano and boy trebles. In casting Oberon as a counter-tenor Britten turned convention on its head, alighting upon the ideal vocal sound, at once strange yet alluring, to suggest the supernatural. The choice of the seraphic counter-tenor voice sent Britten back to his beloved Purcell, whose music (including the semi-opera The Fairy Queen, itself based on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream) he had loved since the early 1940s, and he modelled Oberon’s Act I aria ‘I know a bank’ on Purcell’s elaborate vocal manner.

Oberon’s queen, Tytania, is also a high voice, designated by the composer as a coloratura soprano. Britten’s use of decorative vocal lines for Tytania suggests a further affinity with the music of Purcell. Unlike Oberon’s counter-tenor, Britten’s choice of the soprano tessitura for Tytania lies closer to operatic convention (sopranos are usually the heroines in opera); this is appropriate, for her character has more specific interaction with the natural world than any of the other fairies and in falling in love with Bottom, she crosses into the sphere of the human characters (albeit one with an ass’s head) more than the other supernatural beings.

For his chorus of fairies Britten characteristically employs the robust, at times even aggressive sound of boys’ voices. There is nothing soft-centred or lightweight about their music and its idiomatic character clearly derives from Britten’s long experience of writing for children, especially boys.

Puck, the spirit who flits between the mortal and immortal realms causing havoc, is described by Britten as an ‘absolutely amoral and yet innocent’ figure. Conceived by the composer for an adolescent actor-acrobat, he speaks his lines rather than singing them, though Britten gives him a very particular musical ‘voice’ by associating him throughout with an agile motif on the D trumpet.

Britten’s rustics – Bottom and his companions – lie at the opposite end of the vocal spectrum from the stratospheric sonorities of the fairy world. They balance the vocal hierarchy with their ensemble of male voices thereby making a clear distinction between themselves and Oberon et al. Britten follows operatic convention in his casting of these comic characters, as he does in his vocally balanced quartet of lovers – soprano (Helena), mezzo-soprano (Hermia), tenor (Lysander), baritone (Demetrius) – with Theseus and Hippolyta, who only appear in Act III, supplying the missing voice types of bass and contralto. The vocal balance of the quartet of lovers is at odds with an absence of psychological equanimity for most of the opera, and they nearly always sing in even notes, syllable to syllable.

Britten’s orchestral palette in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is used very broadly to reinforce and evoke the three distinct strata of characters. Puck’s virtuoso trumpet (often supported by a tabor) has already been mentioned; the lovers’ quartet is usually accompanied by a conventional combination of strings and wind, while Bottom and his tradesmen companions are characterized by low-pitched instruments (notably trombone for Bottom himself) or higher instruments playing in their lower registers (e.g. clarinets). To complement the high tessitura of the supernatural characters, Britten reserves specific high-pitched instruments, notably a brace of harps, a harpsichord (a further homage to Purcell), celesta and a small assortment of tuned and untuned percussion, including vibraphone, glockenspiel, xylophone and gong. By such use of tuned percussion, the composer alerts us to the Dream’s magical, other-worldly dimensions, drawing on a tradition that reaches back at least as far, operatically, as Papageno’s magic bells in Die Zauberflöte and reminding us that the dangerous attraction of Oberon is not so far removed from that of Peter Quint in The Turn of the Screw: both these supernatural characters share the celesta as their characterising instrument.

Have a listen to examples of Britten’s mesmerising music with these two clips from ENO A Midsummer Night’s Dream…